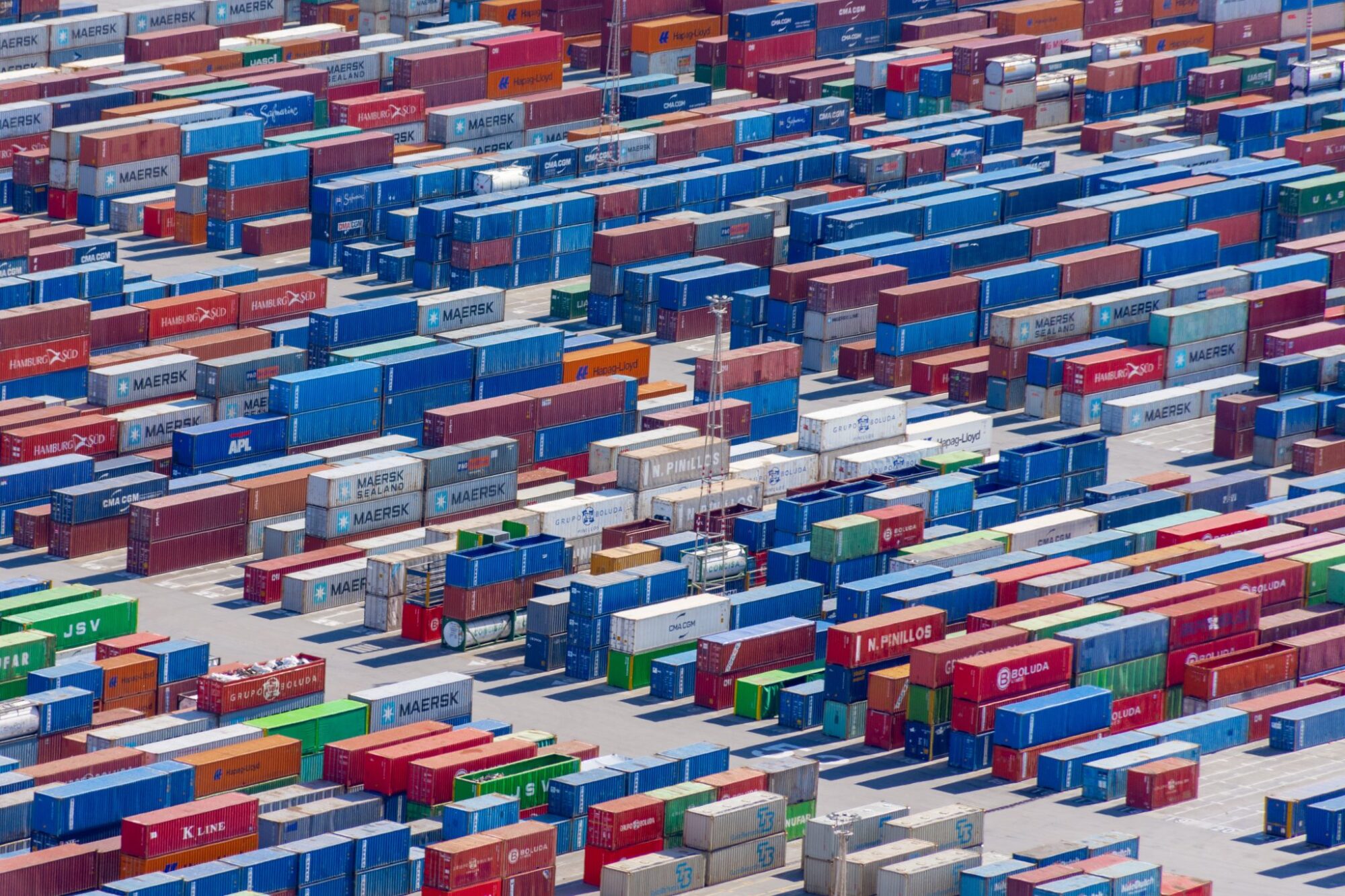

Credit – Unsplash

At the IMO, Countries Float Ideas to Reduce Emissions from Shipping

By: Alex Tesar | October 8, 2024

Shipping connects countries and economies, but it is also responsible for a full 3 percent of our total planet-warming emissions—comparable to a large industrialized country like Germany, and greater than that of the global aviation industry. Last year, the IMO agreed to the 2023 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Strategy, which directed its members to work together on measures to reduce emissions 40 percent by 2030 and reach zero by 2050.

Canada is part of a high-ambition coalition of countries that are pushing for solutions that will make this a reality. Amy Nugent, Oceans North’s Associate Director of Marine Climate Action, joined the Canadian delegation at the most recent round of meetings to advance this work. Before she left, we sat down with her for a Q&A about what was at stake and what it could mean for the health of our waters and our planet. “I am proud to attend as a Canadian and contribute to these crucial conversations for the future of our oceans and global shipping,” she said.

When we caught up with Amy this week, she said some important progress was made, including strengthened consensus on core principles such as incentivizing zero-emission fuels and technologies; having ship owners and cargo companies pay a price for pollution; offsetting the impacts of policies on countries who can least afford it; and retaining funds in-sector to address the energy transition, reduce emissions, and make necessary changes to infrastructure.

However, not everyone agreed on how to realize these principles. For example, there was significant disagreement about whether liquefied natural gas—a fossil fuel— and biofuels could be part of a “decarbonization pathway” for shipping. We don’t think so.

While LNG produces less carbon dioxide than current shipping fuels when it’s burned, it also releases significant amounts of methane across its lifecycle. Methane is a planet-warming gas that is over 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a twenty-year period.

In ships powered by LNG, one important way methane enters the atmosphere is through “slippage” from engines. And a recent study by the International Council for Clean Transportation that conducted real-world measurements of slippage from the most common type of LNG engine found the percentage of unburned methane escaping was almost double what industry had estimated, which would more than negate any climate benefits.

Ultimately, discussions around fossil fuels and biofuels are just another way polluters could slow down a transition that needs to happen quickly if we’re going to avert the worst impacts of climate change. There also is not enough progress or momentum to create effective energy efficiency regulations so that 2030 targets can be achieved.

Ensuring a strong, ambitious plan will require leadership from governments, civil society, and industry. “We need to push for regulations that increase the transparency of industry emissions through rigorous reporting and include binding mechanisms that will actually drive emissions down to zero,” Amy says. “This means closing out efforts to provide sweetheart deals or exemptions for legacy fossil fuel assets and polluting behaviours.”

Amy also said that the efforts and leadership of our colleagues at the Inuit Circumpolar Council, Clean Arctic Alliance, and the Clean Shipping Coalition on regulating underwater noise, reducing black carbon in the Arctic, and creating emissions control areas (ECAs) are producing results.

“Our efforts at the IMO matter for international regulations and they also create incentives to reduce pollution from shipping for our domestic industry in Canada. Environmental leadership is the only path for the Canadian shipping industry to exist and compete long-term,” said Amy.

To learn more about the meetings and why they were important, read Amy’s earlier Q&A. And for more information on green shipping, check out our website.