Protecting Canada’s Muddy Seabed to Mitigate Climate Change

Credit – NOAA

Protecting Canada’s Muddy Seabed to Mitigate Climate Change

Ruth Teichroeb | January 22, 2025

A new study is highlighting the role seabed sediments play in storing carbon and making the case for more protection.

Canada’s carbon-rich seabed sediments should be protected when planning marine conservation areas to help mitigate the impact of climate change and preserve these diverse habitats, a new study says.

Climate change-related marine conservation efforts in Canada have generally focused on vegetated “blue carbon” habitats, such as saltmarshes, seagrass meadows and kelp forests. But new research shows that certain areas of Canada’s seabed sediments contain carbon stocks and burial rates similar to, or even higher than, these more widely recognized carbon-storing habitats. These hotspots—found in fjords, inlets and bays as well some troughs and channels further offshore—cover only around two percent of the seafloor but are estimated to contain total amounts of carbon at least 10 times that of all Canada’s salt marshes and seagrass meadows combined.

“Muddy seafloors may be seen as less exciting habitats than saltmarshes or kelp forests, but they do warrant protection, especially given that they are one of the largest natural carbon stores,” said Graham Epstein, lead author of the study and a post-doctoral fellow in the biology department at the University of Victoria. “We want to boost the attention these habitats get when planning for marine conservation.”

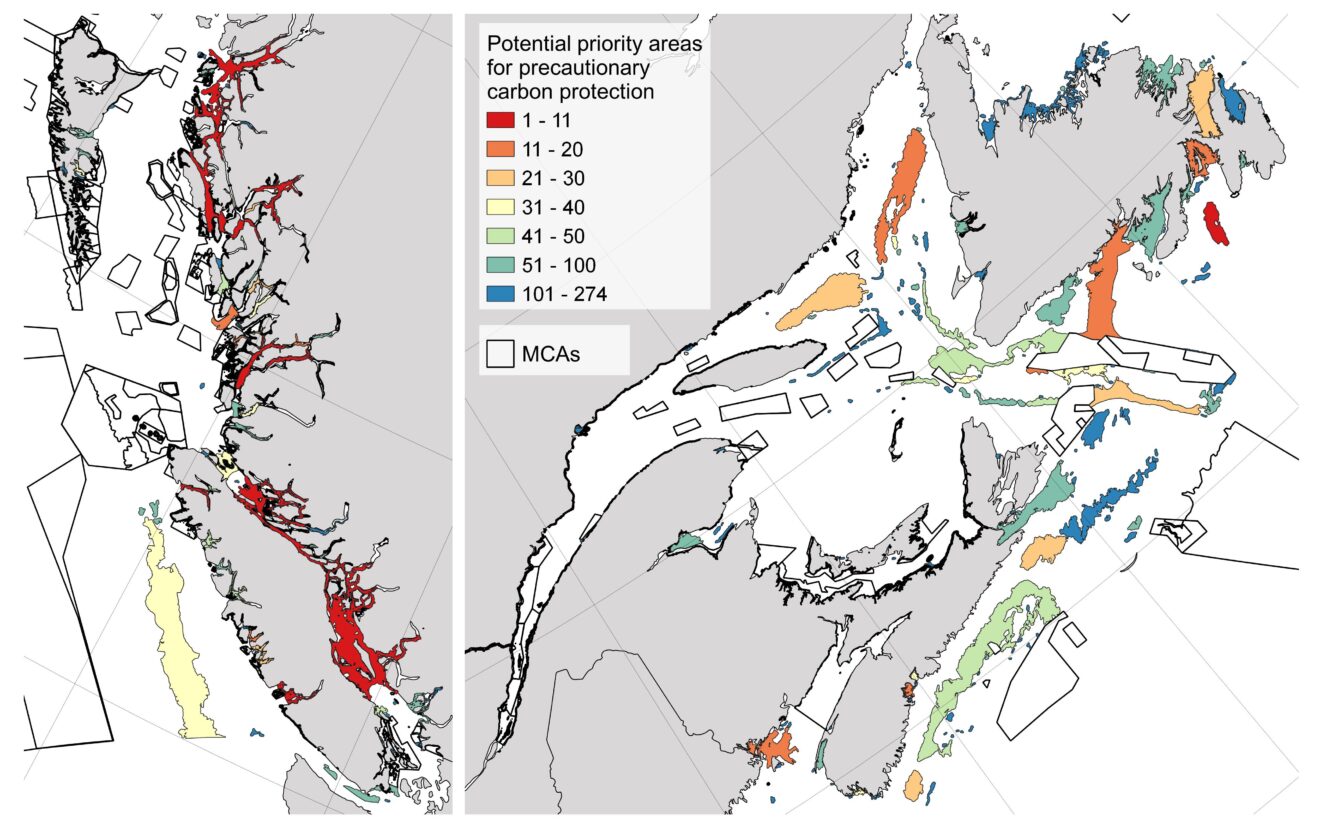

Image – The study identified potential priority areas based on predicted seabed carbon stocks, carbon sensitivity and ecological significance. Highest priority areas in British Columbia (left) include the Queen Charlotte Strait and northern Salish Sea, as well as many of the fjords and inlets on the west coast of Vancouver Island and mainland BC. In the Atlantic, highest priority areas include Placentia, Passamaquoddy, Mahone and Trinity bays, as well as parts of the Laurentian Channel and Scotian Shelf.

Credit – Graham Epstein

The study estimates that only around 13 percent of the carbon-rich seabed sediments are currently included in Canada’s marine protected areas. The federal government has committed to protecting 25 percent of our ocean within Marine Conservation Areas (MCAs) by 2025 and 30 percent by 2030. But while vegetated marine habitats are specifically included in these plans—both for their biodiversity and ability to capture and store carbon—seabed sediments are not.

“Seabeds can be diverse and biologically significant habitats and are at risk of being damaged by disruptive human activities,” Epstein said. “That may include bottom trawling and dredging, which can be widespread and may repeatedly disturb the sediment, as well as construction for energy projects, oil and gas development and shipping.”

When the seabed is disturbed by commercial activities, carbon may be released into the water column and consumed by marine creatures, who then expel the carbon through respiration, potentially increasing the amount of CO2 in the ocean and limiting the ocean carbon sink.

A previous study by Epstein used statistical modeling to create high-resolution maps of predicted carbon stocks in the Canadian seabed and estimated that the top 30 centimetres of sediment on the continental margin hold 10.9 billion tonnes of organic carbon—or around half of all the carbon stored in the trees of Canadian forests.

Using this data, the new study identified 274 priority areas for potential marine protection, ranked by the estimated amount of carbon in the seabed, potential sensitivity of this carbon to being broken down and the ecological and biological importance of the area. At the top of this list were the Queen Charlotte Strait and northern Salish Sea in British Columbia, as well as many inlets and fjords on the west coasts of Vancouver Island and mainland B.C. In the Atlantic region, the highest priority areas included Placentia, Passamaquoddy, Mahone, St. Mary’s and Trinity bays, as well as parts of the Laurentian Channel and Scotian Shelf.

“We are calling for these habitats to be more explicitly included in marine conservation planning, not only for their biological diversity but also for their carbon value,” Epstein said.

While the Arctic is not predicted to contain particularly carbon-rich sediments beyond existing or proposed MCAs, climate change could increase carbon storage in some regions, as well as increase the threats of disturbances from commercial activities. That means precautionary measures could be considered in more carbon-rich areas like the Foxe Basin, Beaufort Shelf and Arctic fjords.

More research is needed to understand precisely how different disturbances on seabed sediments may affect the release of carbon in regions identified for protection. Site-specific mapping of seabed sediment habitats, carbon stocks and carbon burial/accumulation rates will also help with future marine conservation planning, as huge areas of the seafloor have not yet been mapped, he said.

Other partners in the study included Blue Carbon Canada, Oceans North and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Ruth Teichroeb is a regular contributor to Oceans North and is former communications director. She lives in Sidney, B.C.