Northern Latitudes: Mapping Marine Birds in Canada’s Arctic

Northern Latitudes is a series examining how maps and mapmaking contribute to our work.

Even though most of the country is still in a deep freeze, spring is just around the corner. In the Arctic, that means the return of coastal and marine birds that migrate from southern climes to breed each summer.

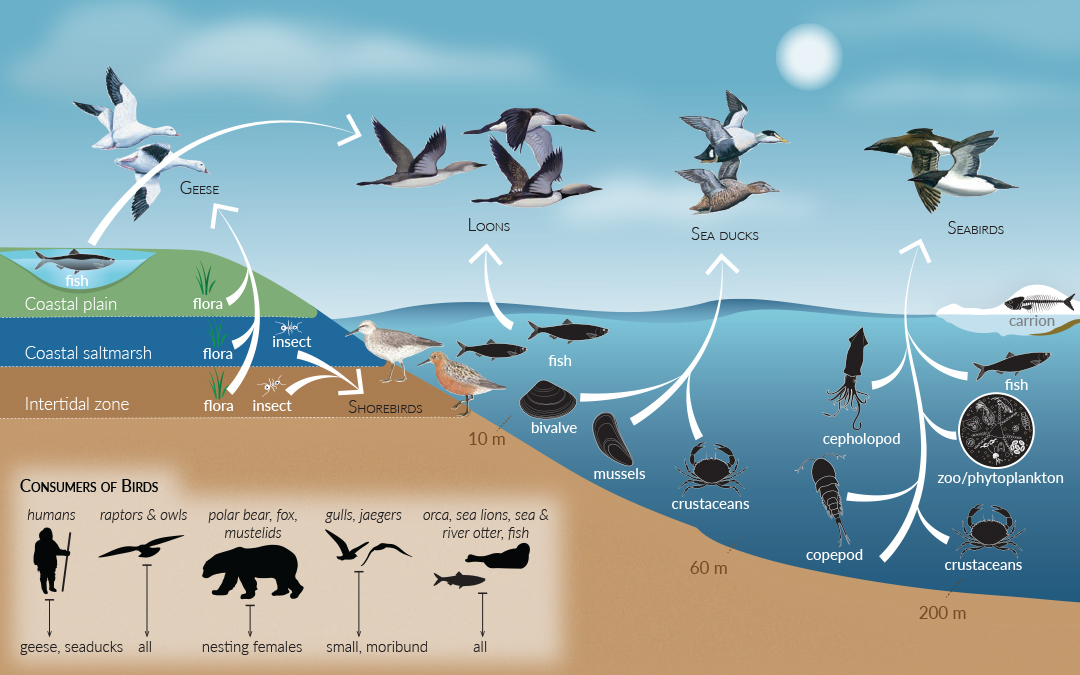

The Canadian Arctic is home to dozens of marine bird species, including seabirds, sea ducks, geese, and loons, that live at the interface between air, land, sea, and ice. Because of this, marine birds not only play a critical role in Arctic ecosystems, but they also serve as useful indicators for the overall health of these ecosystems. Mapping their habitat helps us to better understand factors like changes in food sources and the build-up of contaminants. For example, microplastics and other pollutants in the food web can eventually show up in marine birds, as the graphic below illustrates.

Marine birds are important for northern Indigenous communities as well. Their return in spring represents a fresh source of eggs and meat after a long winter. As well, their skin, bones, and down are used for clothing, tools, and ceremonial purposes.

However, many marine bird species are considered threatened or endangered at a global or continental level. For example, seabirds, a subset of marine birds that includes Ivory Gulls and Northern Fulmar, are one of the most threatened types of birds globally. Nearly half of seabird populations are estimated to be in decline. Marine birds face stressors such as habitat loss (particularly in their winter habitats in more populated areas), as well as threats from hunting, commercial fishing (birds are often caught as by-catch), oil spills, the build-up of persistent pollutants in their bodies, and increasing risks from climate change.

Let’s take a look at two marine bird maps from Canada’s Arctic Marine Atlas which was published by Oceans North. We’ll examine the types of data used to create these maps and where it comes from.

Map 1: Important Bird Areas and Key Habitat Sites

To create Map 1, five different data sources were used including the following:

- Important Bird Areas (IBAs): these are areas that meet certain criteria that have been agreed upon at an international level. These criteria include being home to threatened birds, large groups of birds or birds that have limited range or habitat.

- Key Habitat Sites (KHS): these sites are a designation made by the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), a branch of Environment and Climate Change Canada, for an area that supports at least 1% of any migratory bird species’ Canadian population at any time.

Map 1 clearly shows that important bird areas typically occur on islands where birds can nest or colonize on land while remaining close to their marine food sources.

Map 2: The Prevalence of Common Eiders in the Arctic

Now, let’s turn to Map 2 to learn about a particular species of marine bird: the Common Eider. The Common Eider is an incredibly important bird species in Canada’s north. It is classified as a sea duck and is one of the largest ducks in North America. Common Eiders have a circumpolar distribution of marine and coastal habitats in northern Canada, Alaska, Europe, and Russia. They feed year-round on invertebrates, including mussels. Common Eiders form large colonies on islands during the breeding season and tend to aggregate in larger groups than their cousin, the King Eider.

Credit: Ann Sanderson / Oceans North

Map 2 draws on 15 individual data sources that make up the following data:

- Documented Occurrences: These are places where Common Eiders have been sighted and recorded. This data is useful to show general range but a lack of documented occurrences in a certain area doesn’t necessarily mean Common Eiders can’t be found there. Occurrence data is collected in public databases from a variety of studies, new and old. Some date back decades!

- Documented Aggregations of Nests: These datasets from the Canadian Wildlife Service show documented nesting sites for Common Eiders. These areas may appear limited. But remember, this documentation can only occur where researchers have been able to conduct surveys. There are likely many other nesting sites that haven’t been recorded.

- Breeding and Non-Breeding Range: These are more general areas where Common Eiders are known or expected to occur based on local features such as climate, presence or absence of food, and geography. We can see from the breeding range data that in the summer months, Common Eiders are found in coastal environments throughout eastern and western Canadian Arctic. No wonder they are such an important species to northern communities.

- Designated Sites: These are Important Bird Areas or Key Habitat Sites like those shown in Map 1 that are specific to Common Eiders.

Where Do We Get Bird Data From?

To evaluate conservation status, it’s necessary to understand the population size and habits of birds. However, gathering information on birds, particularly marine species, can be challenging given the large and remote areas where they live. The most common methods for collecting information include bird counts to understand population dynamics and diversity, nest monitoring to assess reproductivity success, and capture and marking to understand migration patterns and survival rates. Capture and marking allows birds to be identified if they are recaptured during bird surveys in the future. When captured, birds may also be outfitted with lightweight satellite or radio transmitters for more detailed migration pattern information.

If you’re interested in learning more about marine birds, check out Canada’s Arctic Marine Atlas for a deep dive into other species.

Olivia Mussels is lead marine conservation geographer for Oceans North.