Why are the Bay of Fundy’s Atlantic Puffins Raising Fewer Healthy Chicks?

Atlantic Puffin carrying hake to feed its chick, Machias Seal Island.

Credit: Joana M. Romero

Over the last two decades, scientists have noticed that Atlantic Puffins in the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine are raising fewer healthy chicks every year. In 2021, for the first time, almost no chicks survived.

Researchers have been monitoring the breeding success and diet of Atlantic Puffins and Razorbills on Machias Seal Island since 1995. They began monitoring Common Murres as well in 2013 after that species colonized the island.

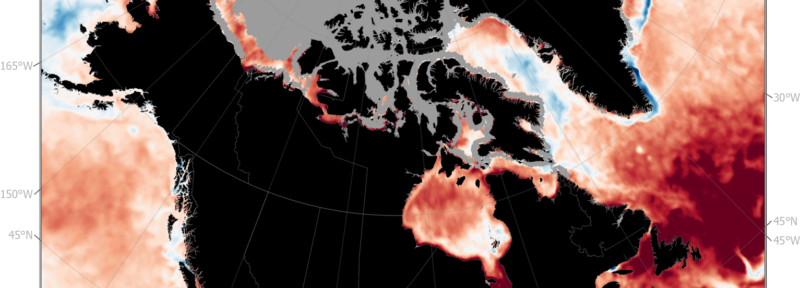

Not much is known about the foraging areas and behaviour of these seabirds in this region. They primarily feed on herring—a fish stock in decline due to overfishing, climate change and other factors. With less herring available, Atlantic Puffins, Razorbills, and Common Murres have been forced to feed their chicks other types of fish that are less nutritious, resulting in reduced breeding success. But the sharpest decline has been among Atlantic Puffins.

Because these species are long-lived, it can take years before changes in population size are noticed. Atlantic Puffins and Razorbills have been known to live to 41 years old and Common Murres to 34. Scientists are concerned because once a population starts to decline, it can be very difficult to reverse that trend. That’s why monitoring programs like the one at Machias Seal Island are important.

Male Razorbill and its chick heading to the ocean, Machias Seal Island.

Credit: Joana M. Romero

Now a new study is underway, partially funded by the New Brunswick Wildlife Trust Fund, to learn more about how climate change is affecting the foraging habits of these three species of seabirds. The study is a collaboration between the University of New Brunswick’s Atlantic Laboratory for Avian Research and Oceans North.

“We want to find out why Puffins are more affected right now, even though they breed at the same time and in the same areas as Razorbills and Murres,” said Joana Romero, a post-doctoral fellow who conducted research over the summer. “Puffins aren’t able to feed their chicks properly and so the chicks are dying or don’t grow enough.”

In order to obtain more information, Romero and others traveled to Machias Seal Island during the last breeding season. Once chicks were more than five days old, they attached GPS trackers to the lower backs of the adult seabirds with tape. For the next three to five days, they collected data about where the birds flew to find food, how many foraging trips they took, the temperature of the water where they caught the fish, how deep they dove and how many times. They also set up cameras to observe what prey the seabirds fed their offspring. This data will allow them to pinpoint the origin of the prey and provide clues about the distribution and abundance of these prey species.

Common Murres and Razorbills on Machias Seal Island.

Credit: Joana M. Romero

Different breeding strategies might also explain why Common Murres and Razorbills had more success raising chicks. Their chicks leave the nest when they are 15 to 20 days old but cannot fly. So they swim away with their fathers who teach them how to forage for prey. By contrast, Atlantic Puffin chicks stay in the nest until they are 30 to 40 days old, and leave on their own.

More data will be collected next year as well, Romero said. “Not only do we want to find out more about puffins to know how to better conserve the species, but seabird research can be used to estimate the health of the herring stock and to help inform herring quotas. Seabirds are good bio-indicators of the health of the ecosystem.”

Ruth Teichroeb is a regular contributor to Oceans North and former communications director. She is based in Seattle.