Rapid Expansion of Mary River Mine Could Undermine Inuit Economic Benefits

Ship docked near Baffinland's Mary River mine in Nunavut.

Crédit : Oceans North

In 2009, when Oceans North started working with Nunavut communities on marine protection for Tallurutiup Imanga, the Mary River iron ore deposit still represented a promise of future northern development. Its potential was no secret. In 1973, Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chrétien was quoted in a speech to the Northwest Territories Council: “I think of the mountain of rich ore at Mary River…uneconomic today but not tomorrow.” Indeed, Inuit leaders selected this land during negotiation of the Nunavut Agreement. In 2010, multinational steel giant ArcelorMittal bought Baffinland Iron and its Mary River claim for $433 million, prompting then Premier Eva Aariak to tell the Globe and Mail: “I hope they’ll invest in our people as much as they’ve invested in the mine.”

Now a new report commissioned by Oceans North and released this week is raising concerns about whether Baffinland’s proposed expansion of the Mary River mine will live up to its promises to maximize Inuit employment and benefits from this project.

In the early stages of Baffinland’s development, there appeared to be little conflict between industrial development and the proposed Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area. At the time, Baffinland said it would ship its ore out of a rail-accessed port built in Steensby Inlet. A shipping route would be established south through Foxe Basin and then east through Hudson Strait (which is not to say that that proposal did not attract its own environmental concerns associated with industrial shipping.) This proposal culminated in an environmental review process led by the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB), and prompted dozens of studies commissioned by Baffinland, Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA), the federal government, NGOs and others.

But Baffinland had already made the internal decision to ship iron ore out of Milne Inlet, just west of Mittimatilik (Pond Inlet). This is a narwhal summering area well-used by local harvesters. Approval for this route was obtained and commercial shipping began in 2015. Originally cast as a cheaper and short-term “Early Revenue Phase,” Milne Inlet has since morphed into a permanent port out of which the company now wants to ship 12 million tonnes per year. Last year, the company shipped 5.1 million tonnes of ore during a three month period. Seventy-one bulk carriers passed through the inlet and Eclipse Sound.

Now, Baffinland, owned by ArcellorMittal and a private equity firm, is seeking permission to ramp up its production and shipping at the Mary River mine. Baffinland hopes production will increase by 600 percent by 2025 – from 5.1 million tonnes in 2018 to up to 30 million tonnes per year until the ore runs out in 2035.

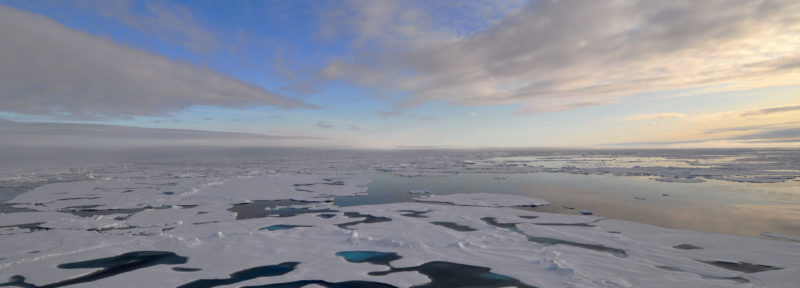

Baffinland's Mary River mine in Nunavut.

Crédit : Oceans North

Does Baffinland’s proposed expansion present a difficult trade-off between increased environmental impacts and economic benefits? That was the question we posed to Dr. John Loxley, a University of Manitoba economic professor. In his report Assessment of the Mary River Project: Impacts and Benefits, he concludes that the relationship between mine expansion and increased local benefits is far from clear. In fact, if the mine expands too quickly, Inuit may not be in a position to capitalize on revenues that should flow from this resource.

The Loxley report suggests:

- The Mary River mine is in all likelihood extremely profitable at present output.

- Inuit employment targets are, by Baffinland’s own admission, unachievable. This is not to say that all efforts to achieve minimum employment targets are not worthwhile, but rather that it is unrealistic to estimate socioeconomic benefits on the assumption that these targets will be met.

- Inuit revenues per tonne of ore will decrease as production volumes increase.

- The lost benefits from the ongoing failure to meet Inuit employment targets could total over 1 billion dollars over the lifespan of the project should Baffinland be permitted to dramatically ramp up output and shorten the lifespan of the mine.

- There is presently no financial compensation that flows to communities when Baffinland fails to meet employment commitments, nor is there a restriction on output.

- While these lost benefits are hypothetically offset by royalty revenue projected to flow to Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (NTI) in the late stages of this development, this constitutes a long-term gamble based on external factors (market conditions, environmental effects, etc.) and ignores the secondary benefits to communities of sustained employment over a longer period.

Emerging scientific data suggest that industrial shipping at current volumes is having profound effects on the marine environment that require more concerted monitoring over a longer period. We do not understand enough about these environmental effects to conclude that further increases are prudent at this time. What we can see from the Loxley report is that, from a benefits perspective, there is no need to rush into expansion.

Christopher Debicki is vice president of policy development and counsel for Oceans North.

Read the report here: