Managing Fisheries in an Age of Climate Change: Atlantic Mackerel

This blog is part of a series on how to incorporate climate change into fisheries management. Click here to learn more and read an introduction to the project.

Atlantic mackerel are an important fish in our region. In the water, they support the entire ecosystem by transferring energy up and down the food chain as a forage fish. The commercial and bait mackerel fishery supplied one of the main sources of bait in the region’s lucrative lobster fishery. Mackerel are also one of the few saltwater forage fish species fished recreationally, supporting both food security and leisure activities for coastal communities. However, the population has been in decline for decades, reaching critically depleted levels in 2011 and falling to further record low levels in 2021. Given its importance, it’s vital that management plans and decisions consider all the threats to this species—including climate change.

With that in mind, Oceans North has demonstrated how to use the pathway we presented in our introduction to the series on Atlantic mackerel management.

The health of the mackerel stock is assessed using an egg survey in the Gulf of St. Lawrence around the summer solstice to coincide with the peak spawning place and timing. This is usually combined with catch, length, and age information. With the closure of the fishery, some of these data are now being collected from mackerel caught incidentally in other fisheries. More information is needed on the prey needs of mackerel and the role they play as food for predators.

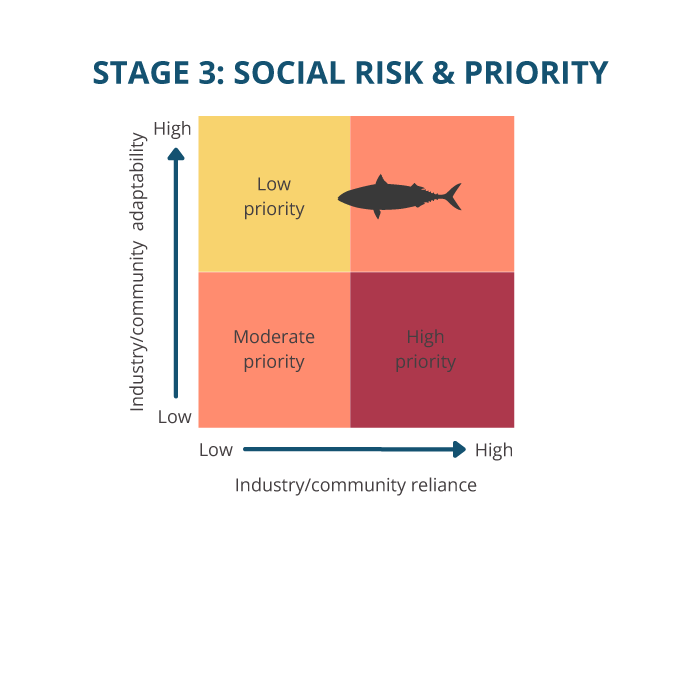

The commercial Atlantic mackerel fishery had a landed value of $7.8 million in 2019, and while the recreational fishery has no landed value, the economic value to the community could be just as high. The value of the bait market is hard to quantify but mackerel are a preferred bait source for the billion-dollar lobster fishery in the Atlantic provinces.

Atlantic mackerel are considered a transboundary and migratory species made up of a northern and southern contingent. The mackerel population spans international waters and is technically a shared stock with the United States. However, both countries set separate quotas while collaborating on science and considering management decisions from both sides. In 2022, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard (DFO) made the difficult but necessary decision to close the commercial and bait fisheries for mackerel for the 2022 season. New science information will be available in 2023 for future management, continued closures and/or quotas.

Atlantic mackerel prefer water temperatures between 9 and 12 degrees Celsius and the northern contingent returns to the Gulf of St. Lawrence every year for spawning in June and July, around the longest days of the year. To date, their peak spawning location and timing as not changed.

According to information in the mackerel rebuilding plan, mackerel’s distribution, survival and growth are known to vary with changes in temperature as well as the availability of prey. Surface and bottom water temperatures have been increasing in Atlantic Canadian mackerel habitat since the 1990s. Furthermore, the biomass of the preferred prey of mackerel, a zooplankton species called Calanus finmarchicus, has been decreasing in the Northwest Atlantic in recent years. These changes are already thought to be negatively impacting mackerel recruitment and condition as they have been below average during the same time period as this environmental change.

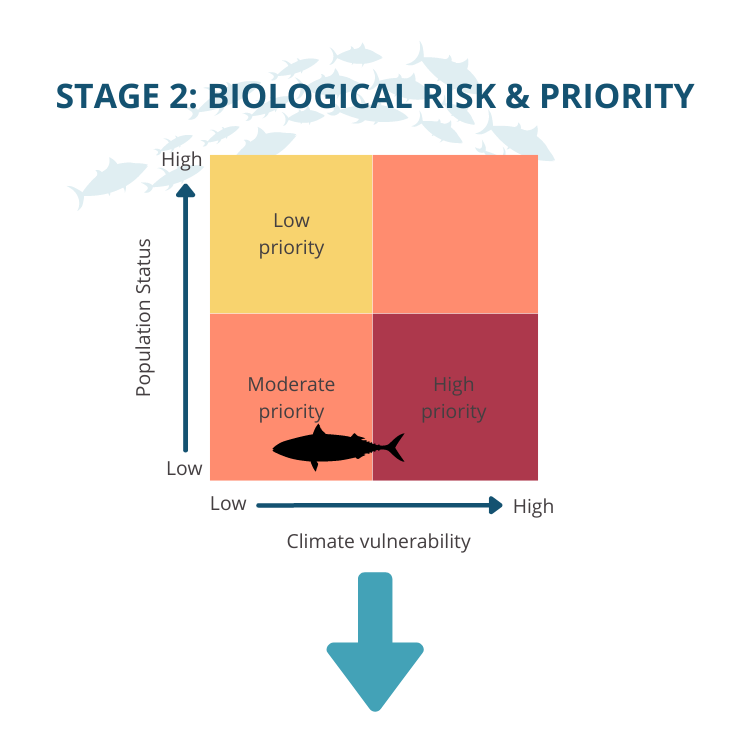

According to the CRIB framework, Atlantic mackerel are predicted to be under moderate climate risk, but with high levels of exposure (the degree to which the species is exposed) and sensitivity (the degree to which the population can be harmed), as well as medium levels of adaptability. This risk of exposure could be mediated by climate mitigation. Conversely, increasing its exposure could move its climate risk to high or critical. Considering this information, we rank mackerel as a medium priority in terms of biological factors.

Landed values of mackerel have been around $7-10 million dollars, representing 0.3% of total Canadian fish landed value in 2013. According to the mackerel rebuilding plan, close to 70 percent of the approximately 600 fishing enterprises who fished for mackerel fish for lobster as their main species. The biggest commercial need for mackerel is as bait, but alternatives do exist and are continuing to be tested with success.

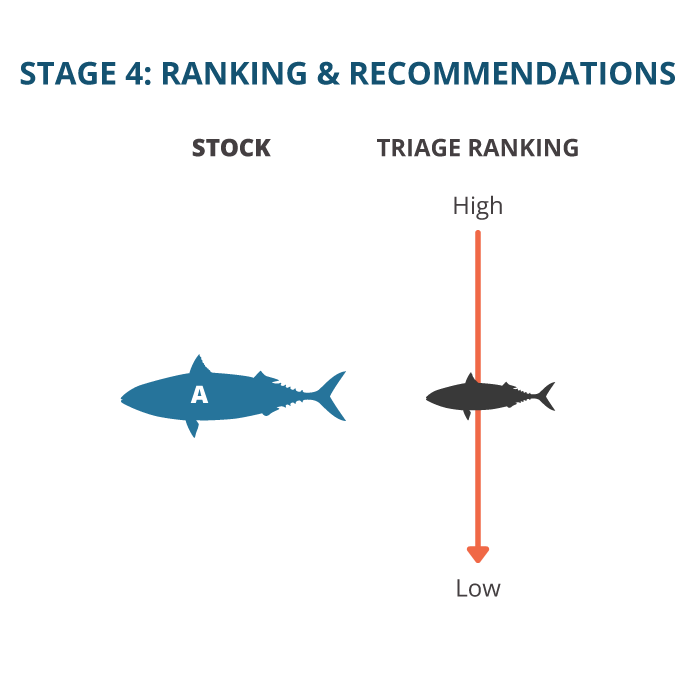

Overall, we’ve scored mackerel at moderate priority for climate adaptation based on biological and social factors. The following are the actions that we recommend that DFO and the industry can take to better adapt to climate change.

The first action to help build the Atlantic mackerel’s resilience to climate change is to allow the population to rebuild out of the critical zone, especially as the average time when mackerel is expected to be adversely impacted by climate change according to the CRIB is between 16 and 80 years from now. Currently, based on the closure of the commercial fishery in 2022, we should be on our way. A healthier stock will not only help the population better withstand climate changes but also provide more stability for industry, as it will make substantial quota decreases or closures less likely in the future. Additionally, rebuilding will increase the value of the fishery to communities, as a healthy stock is likely worth millions more than the recent values of the depleted stock.

One way to decrease the fishing industry’s reliance on mackerel is to develop bait alternatives. Further, when the stock shows signs of supporting a fishery again, managers must consider the ecosystem role and needs of mackerel. This will mean a better understanding of the abundance and location of the Atlantic mackerel’s food sources.

Managing mackerel in the face of climate change will require more knowledge and consideration of the population throughout its range. Canada and the US have increased their collaboration in science and management in recent years, and that should continue and expand as a climate adaptation tool as well. Domestic management will also likely require more flexibility to ensure equitable access to the stock as the population moves due to climate change. Science assessments will also need to expand or adapt their locations and timing to any changes on the stock migration and spawning.

Finally, governments of all levels must continue working on climate change mitigation, as that will ultimately reduce the impacts on Atlantic mackerel and all of those who depend on it.

Next week, we introduce the next species in our series: Northern Gulf cod.

Katie Schleit is Oceans North’s Fisheries Director.