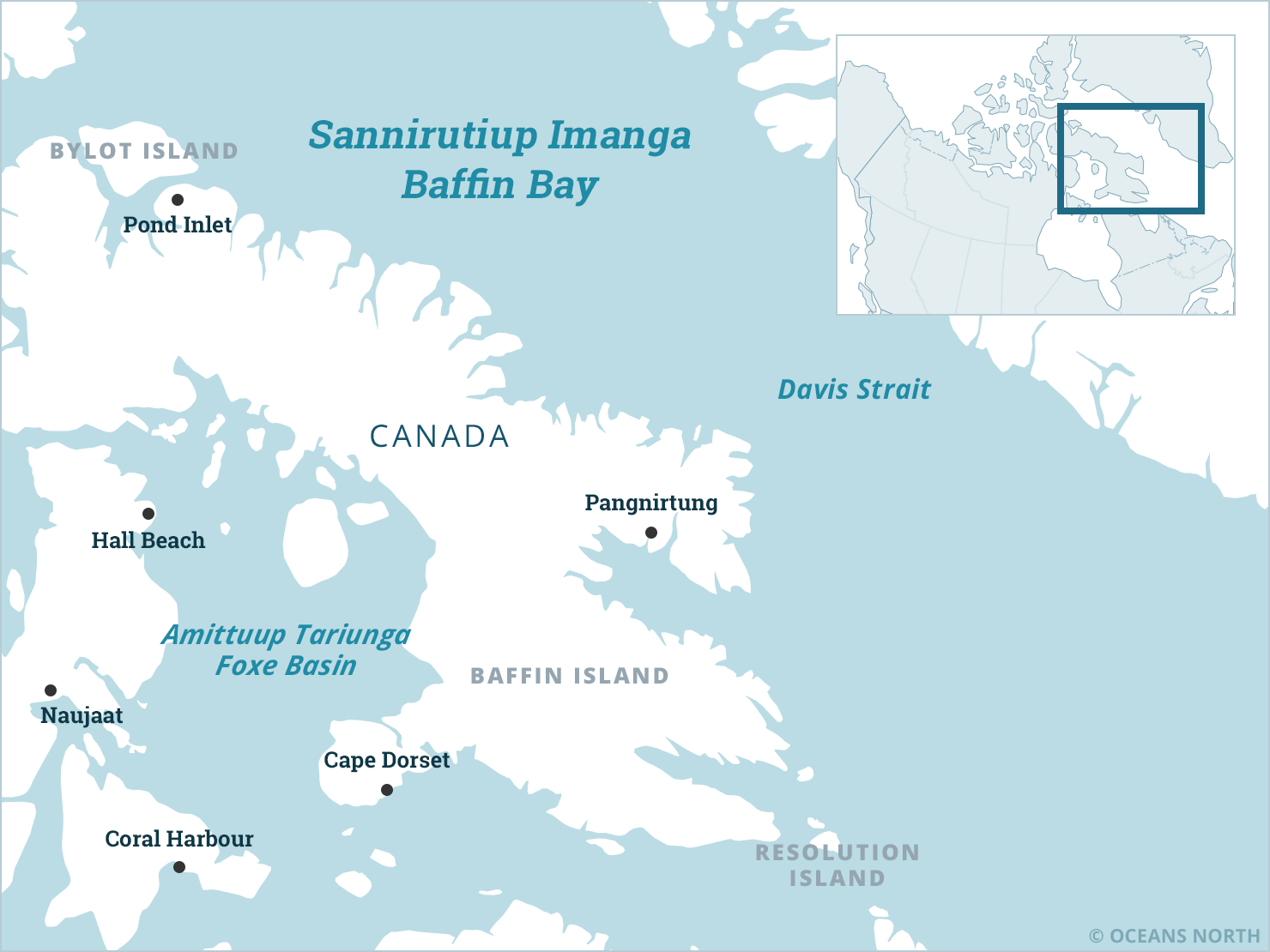

At the eastern entrance to the Northwest Passage, the biologically rich waters of Baffin Bay and Davis Strait have supported Indigenous groups for millennia. Located between Canada and Greenland, these waters connect the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic and stretch over 1.1 million square kilometres.

A strong current that runs up the coast of Greenland and back down the steep Baffin Island shoreline sends cold water and ice southward, creating an Arctic climate as far south as Labrador and Newfoundland. In this icy habitat, marine life flourishes, offering an ideal home for narwhal, bowhead whales, belugas, fish, seabirds and cold-water corals.

A History of Colonial Extraction

Home to coastal Indigenous peoples for thousands of years, this region saw its first European when a Norwegian Viking named Erik the Red arrived in AD 985. His descendants hunted Baffin Bay’s walrus and seals for meat and ivory for over 400 years. After the Viking settlements declined, Dutch and English whalers arrived in the 1700s in search of whale oil; this became a whale oil rush in the 1800s.

While European whaling stations dotted the landscape starting in the mid-1800s, there was no large-scale fishery until well after World War II. That’s when the Soviet fishing fleet, as well as those of Poland and East Germany, expanded globally and introduced the first industrial-size factory freezer trawlers. Foreign fishing fleets were not looking for Greenland halibut (turbot), the mainstay of the ground fish industry in the region today. They sought grenadier and redfish, fisheries that ultimately collapsed in the 1970s and did not recover. After that, the Soviet fleet began an industrial Greenland halibut fishery. At the same time as the grenadier and redfish fisheries crashed, the commercial whale and seal hunts declined. Atlantic Canadian fishermen began to focus on catching shrimp in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. Shrimp trawling multiplied and became even more important in the early 1990s because of the devastation of cod stocks in Atlantic Canada.

The Importance of Sustainable Fisheries

While Inuit and their predecessors have harvested in this region for millennia, they rely on coastal char, shellfish and marine mammals. Commercial open-water fishing is relatively new.

The removal of fish and shrimp stocks directly impacts food supplies for whales that feed in Baffin Bay. Based on stomach content analysis of narwhal, more than 50 per cent of the diet of overwintering whales is juvenile Greenland halibut.

Greenland halibut of the Northwest Atlantic are highly migratory, but the relatively shallow waters in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait are the nurseries for this species. Halibut caught by trawlers in these waters are not mature and haven’t yet reproduced.

Today, bottom trawling operations for shrimp and Greenland halibut in Baffin Bay are Canada’s only industrial Arctic fisheries and these fisheries are complex because the habitat, species and catch allocations are shared between Canada and Greenland. Within Canada, they are also shared among the federal government, the Nunavut government’s Wildlife Management Board and industry. Inuit-owned companies in Baffin Bay have only recently begun addressing inequities in allocation to gain access to fisheries off their shores. The one thing that is clear is that halibut and shrimp quotas have increased over the past decade to the maximum point of sustainable harvest.

A Resource to Be Protected

Oceans North believes that the fisheries in Canada’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), the 200 nautical miles off the country’s coastline, are a common resource to be managed for the benefit of all Canadians, and especially Inuit who rely on this natural bounty.

Because of this, Oceans North supports a precautionary approach to fishery decisions. The goal should be a sustainable harvest to ensure that the populations remain healthy for future generations. Any new commercial fishing must create jobs and infrastructure for Inuit and not impact traditionally harvested wildlife populations. The licensing and allocation process gives the fishing industry access to these resources. In turn, the industry’s primary consideration must be conservation and compliance with relevant land claims agreements.

To protect this valuable resource and prevent overfishing, Oceans North recommends the following:

- Promote the use of innovative fishing gear that protect species at risk and do not harm sensitive cold-water corals. Longlines, for example, limit the bycatch of Greenland shark, skate and grenadier and aren’t as likely to entangle marine mammals.

- Improve scientific knowledge and use accurate reporting, certified observers, satellite tracking devices, air surveillance, ecocertification and Inuit traditional ecological knowledge.

- Consider the impacts on the broader ecosystem when targeting one species and adjust fishing activities accordingly.

- Give priority access to those who live adjacent to the resource.

- Create marine-protected areas that protect Greenland halibut and shrimp stocks.

- Protect ancient cold-water corals and sponges with bottom-trawling closures.

- Approach frontier fisheries with caution by not expanding the commercial fishing footprint past 72 degrees north in Baffin Bay.

Frame of qammaq, or whaler’s home, at Kekerten Territorial Park, the location of an old whaling station near Cumberland Sound, Nunavut.

Credit: Trevor Taylor

Frame of qammaq, or whaler’s home, at Kekerten Territorial Park, the location of an old whaling station near Cumberland Sound, Nunavut.

Credit: Trevor Taylor