Sailing the Labrador Coast While Reflecting on the Fisheries Collapse

There are many ways to see the coast of Labrador. I have seen some of it by snowmobile, a bunch of it by ship, segments of it by Twin Otter and other small aircraft, most of the southeastern coast by longliner and the entire coast twice in an open boat. By far the best way is in an open boat.

The steel structure is all that's left of the old whaling plant at Grady on the Labrador coast.

Ilitariyauyuq: Trevor Taylor

And what a coast it is. From the low, rounded, rocky hills of the southern region to the towering and rugged Torngat Mountains of the north coast it is a spectacle to behold. Running north from the Strait of Belle Isle, one travels waters steeped in history, a history that at once seems distant yet touchable, ancient and only yesterday. Past Fishing Ships Harbour, down through Squasho Run, Frenchman’s Run, along by Punchbowl and Bateau on the way over to Black Tickle, down through Domino Run and then Indian Tickle, across Table and Groswater bays. You pass the Cod Bags, the White Bears, both groups of Wolfs, Triangle, Square, Spotted, Stony, Roundhill and Saddle Islands, Mugford’s Tickle and the Ironbounds, the names on the chart as enchanting as the scenery itself. Ancient peoples going back thousands of years inhabited this land and travelled these waters. Their presence can be seen and felt in so many places along the way and as you look at the diversity and abundance of birds, whales and fish, you know intimately why Indigenous people lived here. And why their descendants remain.

On July 31st, my wife and I departed Gunner’s Cove where I grew up on the northern tip of Newfoundland, very near the historic Viking settlement of Lanse-aux-Meadows, in a 27-foot open boat, bound for Iqaluit, Nunavut. It was my second trip in an open boat and, I think safe to say, for my wife her first and last! At 1100 miles from beginning to end, the five-day trip crossing the somewhat notorious Strait of Belle Isle and Hudson Strait, along with many miles of poorly or hardly charted coast, is not a trip for the faint of heart. But it is beautiful and it was the most efficient way to get our newly acquired boat from Newfoundland to Iqaluit, where we live.

The wooden buildings are the remains of where shore-based cod fishermen or fish plant workers lived while working at a fish plant in Grady on the Labrador coast in the 1980s.

Ilitariyauyuq: Trevor Taylor

Aside from the spectacular scenery, one of the most striking things as you travel the coast is how much of it has been recently occupied for the purposes of the fishery. That may sound odd, especially coming from a former Newfoundland fisherman. True, I had spent much of my younger life on or near the south coast of Labrador. And there are volumes written about the fishery and whaling along that coast. But knowing about the harbours and the bays paints a picture in broad strokes, whereas in the nooks and the crannies you discover the detail. Those with only a cursory knowledge of the coast of Labrador will know about Battle Harbour and Hebron which in their preserved state tell a portion of the stories of this region. It struck me, however, that a lot more of the raw unvarnished story is to be found in the ruins of the deserted nooks and crannies. The preserved history of the coast can be a lot like looking at a dressed-up mummy: it’s easy to miss that this was once a living thing that died and there were circumstances that contributed to that death.

As I said, I grew up a short distance, five miles actually, from the remains of the short-lived Viking settlement at Lanse aux Meadows, a Parks Canada national historic site. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it is a powerful testament to the seamanship of the Vikings and an equally powerful statement to the difficulties of establishing settlement in northern Newfoundland and coastal Labrador. As a boy, I ran over its ruins with my friends on peddle bike, played hide and seek, tag, and took part in childhood mischief there. Looking at the ruins then and now, I imagine the structures that each sodded footprint now represents. This is what I found myself doing as we stepped ashore along the coast of Labrador. For in numerous locations — Punchbowl, Grady and Smokey for example — the remnants of recently occupied structures are found in abundance. In Smokey, the cement footings and pads are just about all that is left of the fish processing plant and support buildings. You stand and look over it wondering what each was used for. Some are relatively easy to identify, others not so much. It is the same in the other coves and inlets along the coast where there are ruins of a bygone time when cod and, in the case of Grady, whales were king.

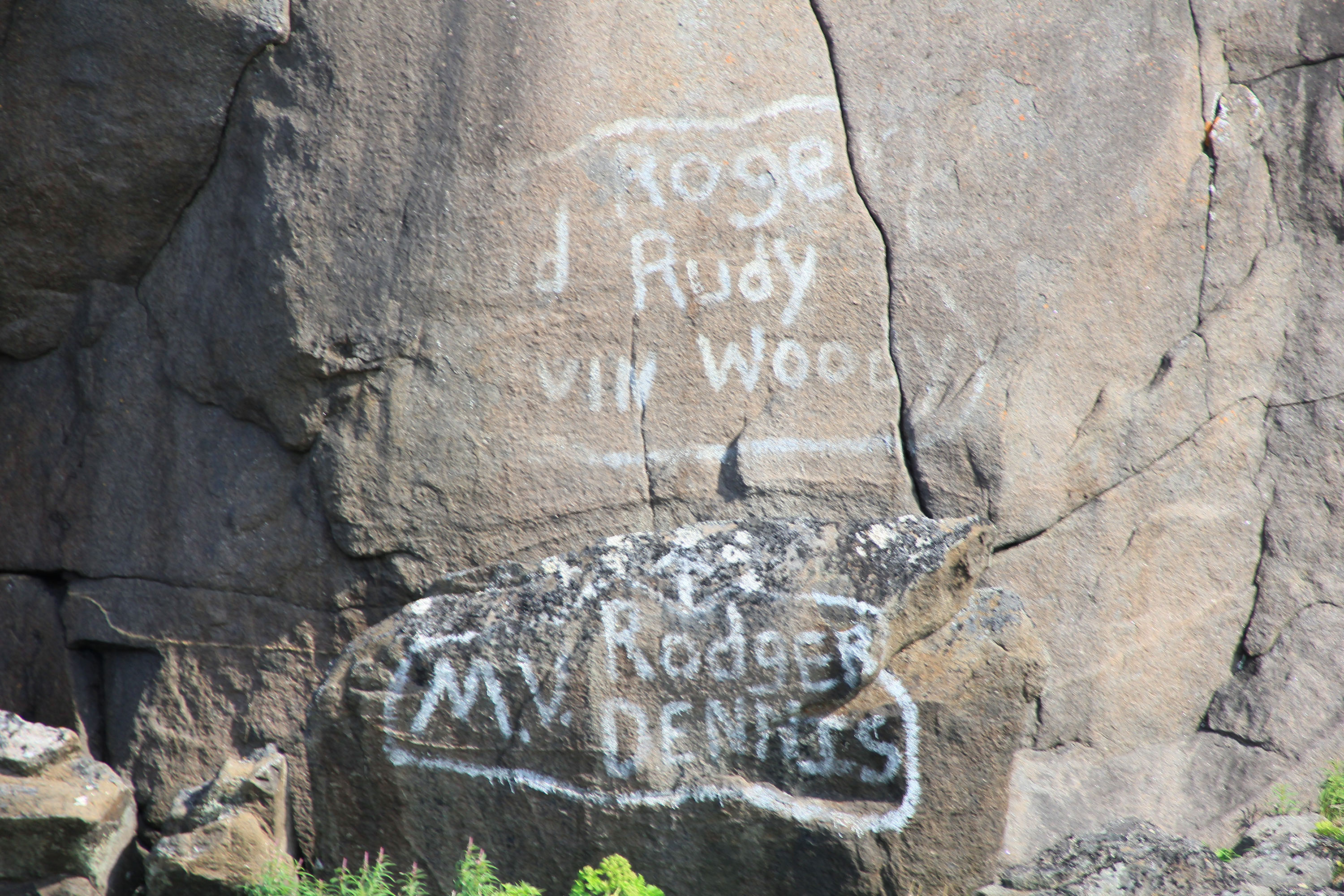

The names painted on the rocks at Grady on the Labrador coast are those of a Newfoundland longliner and its crew who Trevor Taylor knows. He had a fine chuckle when he saw the names.

Ilitariyauyuq: Trevor Taylor

I grew up near Lanse aux Meadows hearing of Smokey. Many Newfoundland and southern Labrador fishermen and, in many cases their whole families, made the annual voyage north to fish from and around places like Smokey. They fished out of Emily Harbour, Indian Harbour, Cutthroat, and countless other little shelters in the rocky coastline. Their story was one of fish, and it lasted, for both whaling and cod, less than 200 years. There were peaks and valleys as a result of environmental changes to be sure. But there is a clearly documented serial decline as a result of overharvesting. Equally well documented were interruption by market conditions, war, extension of the 200-mile limit and moratoria of the harvest allowing for some recovery. But it did not rebuild the fisheries and, in all cases, redirected harvesting pressure surpassed the resource’s ability to produce. It was all finally fished and hunted to the point of commercial collapse and maybe environmental collapse by the late 1980s to early 1990s. Almost 30 years later for cod, and nearing fifty for whales, Smokey, Grady and Punchbowl are powerful testaments to the failure of an industrial model.

You might say it wasn’t really an industrial model. In hindsight that is arguably true, but don’t try to tell that to the people promoting it at the time. It was every bit an attempt to industrialize the coast of Labrador as was tried on the coast of Newfoundland and countless other coasts. And it’s not even that the idea was misguided, as some thought, as much as it was that the proponents were uninformed. While there was a wealth of knowledge about how to catch fish, there was near a void about how much was a sustainable catch. Every collapse of the resource was blamed on lack of information about how to fish just outside the traditional areas. And so with each dip, the methods of harvesting changed and the grounds expanded until finally the truth of total collapse could no longer be denied or escaped.

The remains of an old salt fish plant at Smokey on the Labrador coast.

Ilitariyauyuq: Trevor Taylor

Unfortunately, the other thing that Smokey and Grady remind us of is that it had happened before. Grady and the whaling industry of Newfoundland and Labrador had at least four “collapses and recoveries.” In the early 1970s, foreign fleets decimated the cod stocks off Labrador and Smokey had the biggest collapse prior to the Northern Cod Moratorium of 1992.

This was once a frozen fish plant at Smokey on the Labrador coast in the 1980s.

Ilitariyauyuq: Trevor Taylor

When you stand in these places, it’s easy to question those who made it all happen. As late as 1990, when the cod stock was clearly in serious trouble, both governments were still putting money into Smokey for example. What were they thinking? Well, probably not a lot differently than any number of decision makers in today’s Northwest Atlantic fishery. They didn’t want the resource to collapse, probably thought they were doing the right thing, probably felt they had the information to manage the harvest, or at least to the extent it could be managed. They probably thought they knew better than those who had gotten it wrong before or around them. They mostly viewed year-to-year changes in catch as a factor of environmental influences affecting distribution rather than blaming overfishing. And then, as now, the guiding principle, stated or not, is to manage the fishery at maximum sustainable yield. The problem is, we didn’t know then, and we probably don’t know now, what that is.

You can see a lot from an open boat on the coast of Labrador.

Trevor Taylor is vice-president of conservation for Oceans North.