What Do We Know about the Atlantic Walrus?

A pair of walrus sit on an ice floe near Southampton Island.

ᐃᓕᓴᕆᔭᐅᔪᖅ: Yan Guilbault.

Climate change and industrial development are posing new threats to walruses across the Arctic, including the species known as the Atlantic walrus.

Walrus are an important species for Inuit in many Arctic communities, culturally and for sustenance. Additionally, walrus fill a narrow but critical niche in the Arctic food web. However, despite an abundance of Inuit knowledge on Atlantic walrus, many gaps remain about the species in published data—including the exact size of their populations, the differences between these populations, their seasonal movements, and which summer haulouts they still return to.

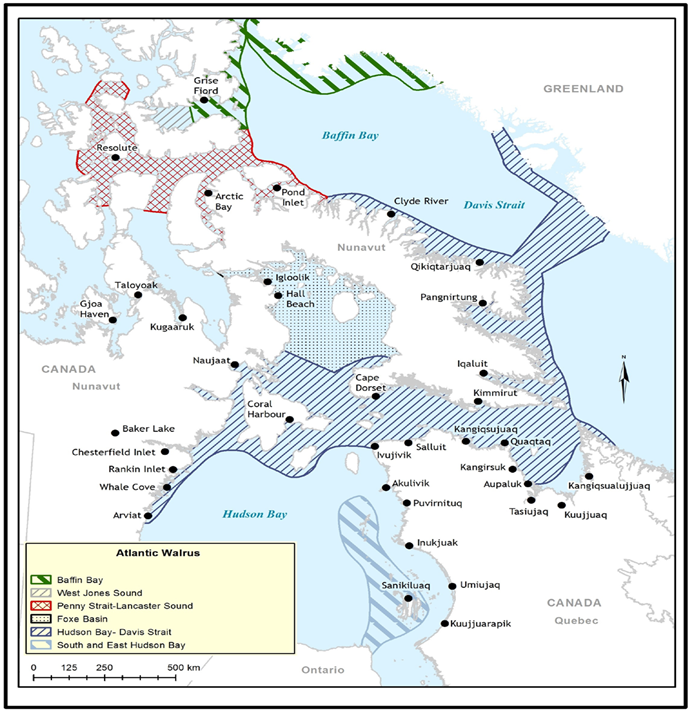

The Hudson Bay – Davis Strait (HB-DS) walrus population lives in northwest Hudson Bay. They’re found throughout the Hudson Strait, as far north as the eastern coast of Baffin Island and as far east as Greenland. It’s this population that Oceans North has recently been focusing on to address gaps in knowledge and to work with communities to protect this species.

Map of walrus stocks recognized by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) in the eastern Canadian Arctic.

ᐃᓕᓴᕆᔭᐅᔪᖅ: Hammill et al. 2016a

What do we need to find out?

Limited data exists about the size of the walrus population, also referred to by scientists as their “abundance.” We do know that in the late 18th century, American and European commercial harvests overexploited this resource and left the central/low Arctic subpopulations depleted. As a result of this overexploitation, the Northwest Atlantic walrus was declared extirpated in 2000. Modern-day abundance estimates rely on sporadic aerial surveys of walruses, as well as satellite tag research (which hasn’t been very successful, as walrus prove to be hard animals to tag). These likely incomplete studies suggest that the total walrus population for the entire central-low Arctic population is about 18,900. The estimate for the Hudson Bay-Davis Straight population ranges from 1000 to 7000.

There is also uncertainty about seasonal movements of HB-DS walruses. Walruses spend their time in the open water, on or near the floe edge, or hauled out on coastal land. Ultimately, two factors determine where they spend their time.

The first is the availability of their prey – benthic invertebrates such as clams, sea cucumbers, worms, and molluscs, which are not well researched in northwest Hudson Bay.

Secondly, walrus distribution is largely determined by the location of ideal haulout areas, which include coastal habitats that range from rocky cliffs to sandy beaches and ice packs. Terrestrial haulouts provide key resting areas for walruses during the summer months when ice is minimal. Many haulout areas—especially those that are far from communities—have not been studied recently, leading to uncertainty about active walrus habitat and distribution.

Another factor that needs to be studied is the impact of climate change on walruses. Climate change has the potential to change the availability of benthic prey, increase polar bear predation, and alter the availability or quality of their habitat. While the projected effects of climate change on walruses will be mixed, they are just estimates at present.

In addition to climate change, walruses are also sensitive to sensory disturbance. Walruses may be able to sense the presence of ships and helicopters from up to two kilometres away. The noise frequency of ships is thought to overlap with walruses’ hearing range, but how they react to these vessels is uncertain. The effects of noise disturbances on walruses are not known but have the potential to initiate stampedes that can cause injuries, interfere with feeding, mask walrus communications, and increase stress levels.

Where do we look for more data?

Considering the gaps in knowledge of walrus abundance, seasonal movement, and the potential effects of climate change and disturbance on walrus, it is clear that more research and knowledge collaboration is needed in order to ensure that these incredible creatures remain abundant in their traditional habitat. Inuit participation in sharing knowledge and shaping research will be critical to improving our overall understanding of Atlantic walruses. For example, hunters—both past and present—can help identify active haulout areas and improve knowledge about the characteristics of walrus populations and the changes they’ve seen throughout the years.

In addition to Inuit knowledge, previous studies can help inform future research. Oceans North is currently reviewing a 30-year data set of a study carried out on Coats Island in Hudson Bay. The data, while focused on Arctic birds, includes frequent observations on the HB-DS walrus population. Notes on walrus movement, abundance, haulout areas, and hunting techniques have been recorded on the island for decades. While this data is only observational, it helps identify key habitat areas and allows us to better design future research questions.

What protection is there for Atlantic walruses?

Walruses rely on multiple habitats: marine areas for travel, feeding, and reproduction; ice for resting and reproduction; and land for resting and feeding. Because of this, walrus protection crosses multiple jurisdictional boundaries at municipal, territorial, and federal levels.

Local Hunter and Trapper Organizations throughout the Arctic can set harvest rules and regulations to reduce walrus disturbance. At the territorial level, the Nunavut Planning Commission is working to create a Nunavut Land Use Plan that includes protection for walrus haulouts. At the federal level, multiple national parks, wildlife areas, migratory bird sanctuaries, and Marine Protected Areas exist throughout the Arctic, but most of them are located in the high Arctic, leaving central/low Arctic walrus populations largely unprotected.

Closing knowledge gaps is an important step in improving protection and management of Atlantic walruses so that they can continue to fill their ecological niche in marine environments, provide sustenance, and remain integral to Inuit culture for generations to come.

Kelsey Crouse is completing a work placement at Oceans North as part of Carleton University’s Northern Studies program.

To learn more, read the technical report “Atlantic walrus (odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) in northern Hudson Bay Status, research needs and monitoring opportunities” in the resources section of our website.