Managing Fisheries in an Age of Climate Change: Northern Gulf Cod

This blog is part of a series on how to incorporate climate change into fisheries management. Click here to learn more and read an introduction to the project.

Landings after the 2003 moratorium increased steadily but fell again to an average of 1,285 tonnes between 2012-16 against a TAC of 1,500 tonnes.In 2010, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) designated the stock as endangered because adult abundance had declined by 78-89 percent over three generations (30 years). Since the stock has been in the critical zone of DFO’s precautionary approach framework since 1990 and shows little sign of recovery, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard (DFO) declared yet another closure of the fishery in 2022, this time over a 1-year management plan.

Northern gulf cod is on the batch 1 major stock list, which means DFO is legally required to create a rebuilding plan that helps the stock recover. Nonetheless, DFO has still not released a rebuilding plan and time is running out.

Cod are part of a group of species commonly known as “groundfish,” which are fish that spend most of their adult lives on or near the seafloor. Adult cod have a broad geographical distribution and can be found in a wide range of water temperatures. However, 12°C is the maximum temperature cod can tolerate over an extended period time. Juvenile cod have a significantly decreased thermal window and are more vulnerable to temperature changes.

Climate change has caused water temperatures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to increase by 2°C from 1990 to 2014, which is having an impact on the abundance of plankton and cod prey species such as capelin, herring, and mackerel. A reduction in prey species will ultimately result in reduced changes of survival (higher natural mortality) for adult cod and future populations. If global warming exceeds 1.5 °C, it could trigger multiple climate tipping points which can disrupt entire ecosystems.

Under the CRIB framework, Atlantic cod was found to experience moderate-to-high climate risk across its range and is at high-to-critical risk in the Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence. However, under a low or mitigated greenhouse gas emission scenario, the spatial extent of climate vulnerability and risk for cod is reduced. Therefore, if no action is taken regionally or globally to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, northern gulf cod will be severely impacted.

Another driver likely contributing to the decline of the northern gulf cod stock is natural mortality via unrecorded fishing and predation by grey and harp seals. While not found to be the main factor in preventing recovery (as is the case with the separate Southern Gulf (4TVN) population), natural mortality and seal predation likely put this population at even higher risk.

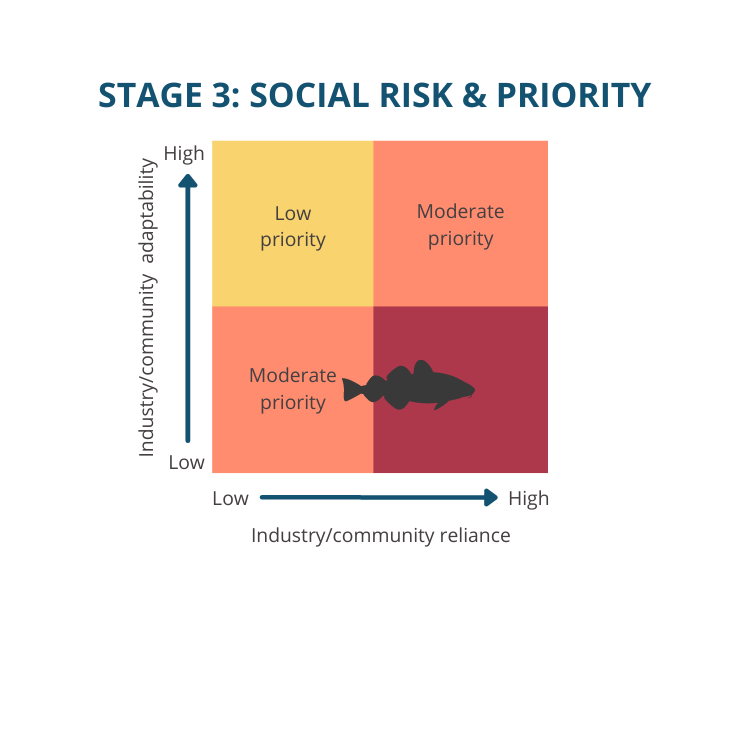

Considering the socio-economic factors in the commercial fishery, northern gulf cod are a moderate-to-high social risk based on the industry’s ability to adapt and the reliance of the industry on cod.

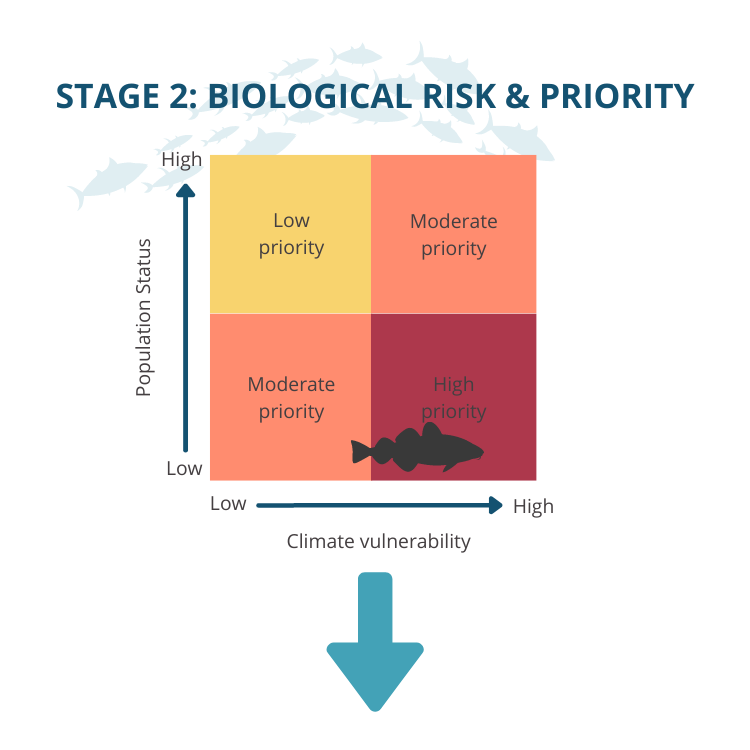

Overall, we’ve scored northern gulf cod at high priority for climate adaptation based on biological and social factors.

To become more resilient to climate change and to mitigate subsequent socio-economic impacts, the northern gulf cod fishery needs to rebuild out of the critical zone. The closure of the commercial fishery in 2022 is an important step towards this goal, as fishing is the main variable we can control. Fishery managers also need to create and implement a robust rebuilding plan with tangible goals to build the stock above the Lower Reference Point (LRP) as part of the precautionary approach framework. To address the natural mortality stress on the population through seal predation, DFO needs to move towards ecosystem-based management that incorporates food webs.

Managers need to provide resources for harvesters to refit their vessels with low-emission technology, which could be done through rebates or buy-back programs. Managers also need to allow time for the fishing industry to explore other options for supplementing their income with non-fishing activities, to diversify their current fishing licences, and/or to offer training to fishers who want to diversify their professional skill sets.

Lastly, managers should allow the transfer of fishing licences to other stocks and/or fishing areas due to climate change vulnerability and stock collapse. New fishing opportunities could also be exploited as long as these fisheries are properly assessed and managed. Warm water species such as blackbelly rosefish and John Dory have been found in DFO bottom trawl surveys in increasing numbers on the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy, which lie to the southwest of the Northern Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Stay tuned for the next species in our series: American lobster.

Gemma Rayner is Oceans North’s Fisheries and Special Projects Advisor.